China’s tech firms in limbo amid COVID resurgence, US scrutiny

March 17, 2022

Porsche to build out its own network of EV charging stations

March 18, 2022

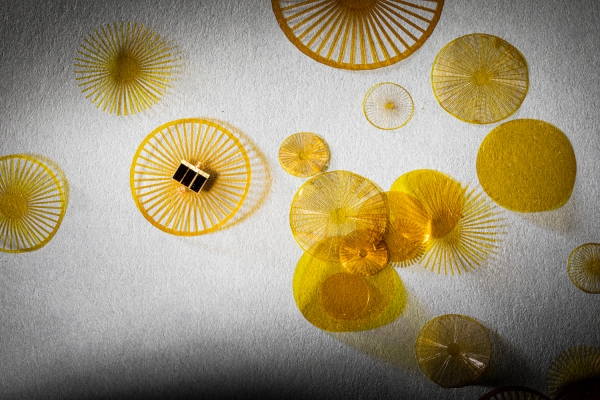

If you want to monitor the temperature, humidity and exposure over 100 square miles of forest, you’re going to spend a lot of time tying tech trees. But what if you could scatter your sensors the same way dandelions and elms scatter their seeds? UW researchers have put together devices light enough to be carried by the wind.

The project pushes the boundaries of small-scale and purpose-built computing, and while it’s still very much a prototype, it’s an interesting direction for embedded electronics to take.

“Our prototype suggests that you could use a drone to release thousands of these devices in a single drop. They’ll all be carried by the wind a little differently, and basically you can create a 1,000-device network with this one drop,” said Shyam Gollakota, a UW professor and prolific device creator.

It’s made possible primarily by the removal of any sort of battery, which lowers the mass of the electronics considerably. Equipped with only a few tiny sensors, a wireless transceiver and a couple tiny solar cells, the gadget itself weighs less than 30 milligrams.

Its wind-catching structure was arrived at after dozens of attempts, ultimately arriving at this bike wheel shape as one that both caused the device to travel far from its starting point but also land with the solar panels facing upward 95% of the time. When scattered by drone, they can travel some 100 meters before settling down.

Once they land, they will operate whenever it’s light, using radio-frequency backscatter to bounce their signals off the environment and to each other, forming an ad hoc network that can be collected by a control device.

It’s nowhere near the mobility of the miraculously light dandelion seed, which weighs a single milligram and can travel for miles. But nature has had eons to perfect its designs, while the team at UW just started recently. The other challenge is, of course, the fact that real seeds eventually either turn into dandelions or decay into nothing — while a thousand sensors would remain until picked up or broken to pieces. The team said they’re working on that, though the field of biodegradable electronics is still young.

If they can figure out the e-waste angle (and probably the animals eating them angle), this could be very helpful for people trying to keep a close eye on threatened ecosystems.

“This is just the first step, which is why it’s so exciting. There are so many other directions we can take now,” said lead author Vikram Iyer. The paper describing their work appeared today in the journal Nature.

DroneSeed’s $36M A round makes it a one-stop shop for post-wildfire reforestation